Parasol playground in winter. Photo: Armin Schuhmann, March 7, 1978

In the second half of the 19th century, large urban parks were created in North American cities. These vast spaces were designed for the contemplation of nature; our own Mount Royal Park is an example, offering an oasis for leisure amidst the hubbub of the metropolis. Inspired by the City Beautiful Movement, municipal leaders developed numerous parks and public squares, which were also designed to provide for the moral uplift of their citizens. Real estate developers could not help but notice that such green spaces adjacent to building lots considerably increased their value. In Montreal, the bourgeois suburbs of Outremont and Westmount offer perfect examples of this type of land development.

In the western portion of Mile End, called The Annex at the time, this was a missing link of the upscale residential project launched in 1891. From then until 1908, developers and residents sent numerous petitions to the Saint-Louis town council seeking to obtain a park on the empty lot located between Fairmount, Park, Laurier and Esplanade avenues, which in 1920 became the site of B’Nai Jacob Synagogue—now one of the buildings occupied by Collège Français. The petitioners emphasized that Fletcher’s Field (today’s Jeanne-Mance Park) was too far to allow children to go there, unless part of a supervised excursion lasting at least a half-day.

The debate resurfaced 25 years later, in a different form. The Annex had lost its character as a suburb reserved for the middle classes, and had become a densely populated working-class neighbourhood, primarily Jewish. By the beginning of the last century, reform groups such as the Montreal Parks and Playgrounds Association had been calling for parks as playgrounds, “to get children off the street.” Organized recreation had become an instrument of social integration, designed to counter unhealthy idleness and fight against juvenile delinquency. On July 8, 1932, the Canadian Jewish Chronicle published an open letter from a group of parents living on Esplanade Avenue. They reminded municipal officials that they had not fulfilled their promise of creating a playground. The parents denounced the fact that their children had nowhere other than the streets or alleys for play; in addition, the Fairmount School yard—now also a Collège Français building—was kept locked. This part of Mile End, located north of Laurier Avenue, was then known as the Saint-Michel district. Prior to every city election, candidates campaigned on the claim that Saint-Michel was a forgotten neighbourhood. Between 1921 and 1940, they all promised a public playground, but one was never created.

Photographs taken by Conrad Poirier in 1942 reveal that the Park Avenue YMCA (then called the North End YMCA) came to the rescue. It created a playground on the empty lot adjacent to its building. But sometime during the 1950s or 1960s, the playground disappeared. Expansion of automobile use led to its transformation into a parking lot, probably for the use of Y employees who had migrated to the suburbs. The loss of the playground was not an indication that there were fewer children in the neighbourhood, on the contrary. Mile End was then a district of newly arrived immigrants, who were starting at the bottom of the ladder. The neighbourhood was considered one of Montreal’s poorest at the time—to such a degree that, at the end of the 1960s, the YMCA decided to make social work in the neighbourhood one of its priorities. It hired workers to organize recreational activities for the children of these primarily Greek immigrants. Activities took place in the alleys because, as one child related later, there was nowhere else to play outdoors.

Children playing at the North End YMCA playground, Park avenue. Conrad Poirier, July 10, 1942. BAnQ P48 S1 P7518

Conrad Poirier, July 10, 1942. BAnQ, P48 S1 P7517

In spring of 1973, parents got together to create the Esplanade Street Association. They called on the city to make the streets safer for children by better managing traffic, e.g., by adding flashing lights. They also wanted a playground created. After a series of pressure tactics—including a petition with 600 signatures and the blocking of Van Horne Avenue— they were promised a playground. But, a year later, the group spokesperson noted that nothing had been done. One of the Street Association’s members, a young architecture student named Marilyn Montblanch, convinced the YMCA to recreate the Park Avenue playground. In 1976 she, together with the Esplanade parents proposed “Projet Parasol”. The idea was to transform the Y parking lot into a mini-park and café-terrasse. The park opened on July 6, 1977, for use by the children and counsellors of the YMCA day camp. In the evening it was used for a café and performances organized by neighbourhood community groups.

YMCA parking lot, before the conversion into the Parasol playground. Photo: Marilyn Montblanch.

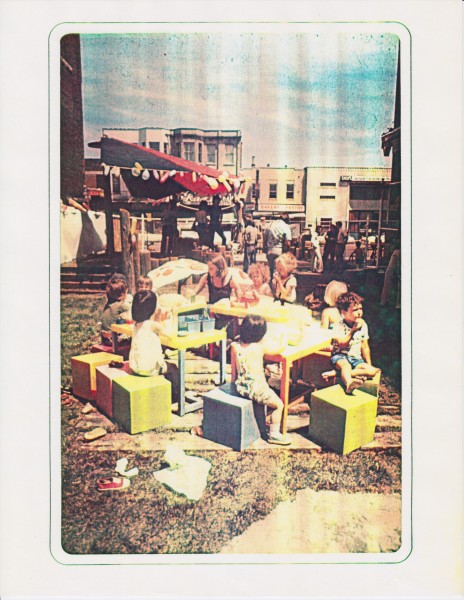

Children’s show, parasol playground. Photo: Marilyn Montblanch

However, Parc Parasol disappeared during the 1990s. The Y building, constructed in 1913 and by then in disrepair, was demolished in 1993, to be replaced by the current building. Parc Parasol’s location was occupied by the indoor swimming pool. But the years of mobilization by neighbourhood residents started to bear fruit. In 1987, the YMCA collaborated with the Mile End Citizens’ Committee and the Anglican Diocese of Montreal to create a mini-park a few steps away, beside the Church of the Ascension. It is still there today, known as Mile End Park, adjacent to the Mordecai-Richler Library. Toward the end of the 1980s, the City of Montreal designated the neighbourhood as a “priority sector for recreational facilities.” In 1987, a playground added to the parking lot of Edward VII School was officially given the status of a school-park. Clark Park—now known as Lhasa-De Sela Park—was a residual space, more or less abandoned, which was left over from properties expropriated to construct the Rosemont—Van-Horne overpass and the Saint-Urbain Street tunnel. The park was inaugurated in the mid-1970s and redesigned in 1999. Toto-Bissainthe Park, named for a Haitian singer, was also created around 1980. It is located at the northeast corner of Hutchison and Van Horne.

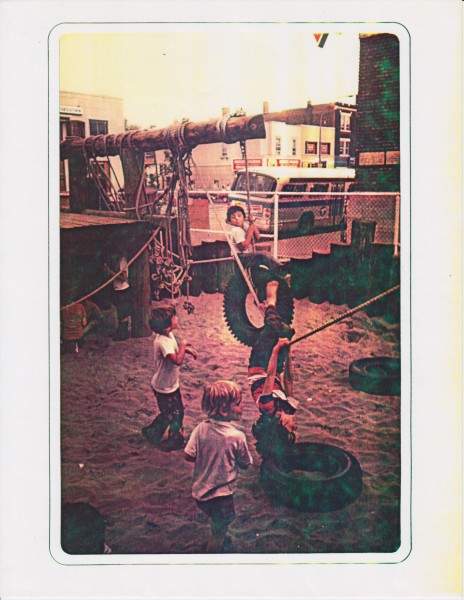

Children’s games, Parasol playground. Photos: Marilyn Montblanch

Translation: Joshua Wolfe

Sources:

“New Park Proposal Crops Up Again”, Montreal Daily Herald, July 4, 1908, p. 15.

“Esplanade Avenue”, Canadian Jewish Chronicle, July 7, 1932, p. 9.

Interview with Andrew Gryn, September 2015.

“Parents demand safety improvement”, The Gazette, April 14,, 1973, p. 3; “Esplanade parents get pledge”, The Gazette, August 17, 1973, p. 3; Shirley Curtis, Chairwoman, The Esplanade Street Association, letter to the editor, The Gazette, October 31, 1974, p. 8.

Interview with Marilyn Montblanch, October 2015.

Damaris Rose, “Le Mile End, un quartier cosmopolite?” in Annick Germain, ed. Cohabitation ethnique et vie de quartier. Rapport final soumis au ministère des Affaires internationales, de l’Immigration et des Communautés culturelles et à la ville de Montréal, Les Publications du Québec, 1995, p. 64.

Thank you Yves, Joshua and Justin for the opportunity to bring Projet Parc Parasol back to life! If anyone has memories of being a parent, child or animator at the Y (International) during this time, I hope you can share them.

The black & white photo was taken by Armin Schuhmann while he was a student at MIND, a newly formed alternative high school, housed on the top floor of the Y at that time! In the evolution of Parc Parasol I remember seeing a vegetable garden there, made by a youth group (or perhaps the MIND students)…

Merci Yves, Joshua et Justin d’avoir permisent à Projet Parc Parasol de renaître dans les pages de Mémoires du Mile End.

Si vous avez des mémoires d’y avoir joués ou participé aux activités du Parc Parasol, partagez-les s.v.p.

L’école secondaire alternative MIND, se trouvait à l’époque, au 3ième étage du YMCA (International) – Armin Schuhmann, alors étudiant à MIND, a pris la photo du patinage en n&b… belle surprise pour moi qui a connu le parc que en été!

I would be curious to know the history of Parc Alphonse-Télesphore-Lépine, Parc St Michel, Parc du Carmel and surrounding streets. Do you not consider this part of Mile End until recently, or were there fewer families living in this area?

The area around the parks you mention is certainly part of Mile End. However, in the 1970s and 80s, there were indeed fewer families in the area – or at least fewer families who were politically active and engaged. Although the east side of Saint-Laurent Boulevard was originally developed earlier than the west side, this part of the neighborhood was the last to be fixed up, toward the end of the 1990s. Also, it was relatively easy for the city to find space for parks on the east side as industries left the area. On the west side, land was scarcer and battles had to be fought to obtain playground space.

It’s true it would be interesting to tell the story of those three parks, the green necklace of eastern Mile End. We’ll see what we can do!