With this article, Mile End Memories begins publication of an essay on the history of the neighbourhood, written by Yves Desjardins. During the next few months, we will be posting the various chapters on line. Even if the neighbourhood has been the subject of many articles and studies, until now, this information has not been synthesized in one paper. That is the goal of this publication.1

The Mile End neighbourhood, comprising the northwestern part of the Plateau Mont-Royal borough, has been labelled one of the planet’s “trendiest districts”.2 As an incubator of new trends and the alternative scene, it has even been subject to university research.3

However, for nearly a century, Mile End was first and foremost a transitional area: a point of arrival for several generations of immigrants for whom leaving the neighbourhood – which they associated with their first impoverished years in the country – was often the primary goal. The Peck Building, at the corner of Saint-Laurent and Saint-Viateur, captures this transition and today’s changes to the district. For generations, it housed successive waves of Jewish, Italian, Greek and Portuguese immigrants, working for little pay in its clothing factories. Now it is the Canadian headquarters for Ubisoft, with its worldwide army of programmers, developers and designers.

Exploring the roots of the neighbourhood reveals that it is precisely this status as a gateway which has made Mile End a unique place. From the turn of the last century, a cohabitation of various ethnic groups speaking various languages, belonging to different social classes and diverse religious traditions has been the norm. A kind of no-man’s land between Catholic French-Canadian districts to the east and the Anglo-Protestant west, Mile End was a place of social and cultural mixing, on which the stamp of several generations is still visible.

These waves of immigration can be summarized as follows:

—1850–1890: a village on the outskirts of the city which was already divided between eastern and western sectors by Saint Lawrence Street. On the east, Francophone Catholic labourers and artisans, living near their place of work (primarily the quarries). Further west was an agricultural zone, which was also used for rural recreation by the Anglophone élite, owners of country homes, orchards and hunting grounds.

—1890–1920: the second phase of the industrial revolution brings rapid urbanization to the entire sector. While the eastern side remains largely working-class, in the west, ambitious developers attempt to create a suburb for the new middle class comprised of white-collar workers (“The Annex”).

—1920–1950: Montreal’s second wave of Jewish immigration; they were called the “downtowners”, in contrast with the “uptowners” who had arrived in the 19th century and were more assimilated. The second wave came from Eastern Europe and settled heavily in the neighbourhood, at a time that coincided with a golden age of Yiddish culture.

—1950–1980: the Jews moved away, replaced by new waves of immigration in the post-war period: Ukrainians, Greeks, Italians and Portuguese.

—1980–2013: the current wave, which may be described as a “return”, because often the children of those who left Mile End have returned, giving it its contemporary character.

Prologue: My father’s neighbourhood

A child of the post-Second-World-War suburbs and the baby boom, I was raised in Laval in an environment where we all seemed the same: Francophone and Catholic. In fact, we did have Jewish neighbours: the Hecklers, Anglophones originally from Austria. Later I realized they were undoubtedly refugees from a Europe devastated by war and anti-Semitism. Our relationship was polite but remote; one of my childhood memories was of travelling to their small pastry shop, the only store in the area that was open on Sunday.

My parents, on the other hand, had grown up in a much more multi-ethnic environment. My mother came from Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, mainly populated by middle-class Anglophones in the inter-war period. This allowed her to become perfectly bilingual. My father’s childhood and adolescence was closer to poverty: he told us of a poor, grey neighbourhood, marked by the massive unemployment of the Great Depression of the 1930s. In his memories, the district took on a mythical quality: how he was able, thanks to his studies and work, to leave it – his upward mobility confirmed by his marriage to my mother, from a higher social class, and by the suburban environment, part of the North American dream he was able to provide his children. But at the same time, the stories of his childhood memories described a universe that was much more colourful, lively and noisy than the uniform suburb where I was growing up. It was also a universe marked by deep social divisions, exacerbated by differences in language and religion.

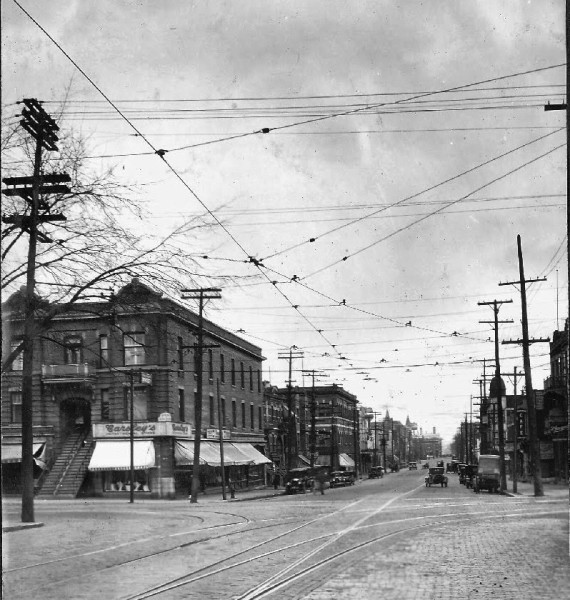

So in 1973, it became my turn to move to that neighbourhood, Mile End. It was 20 years after my father had left. I remember he was unable to understand why his eldest son would return to the very site of the poverty and misery he had fled. And it is true that at the time Mile End was down at the heels.4 As a 19-year-old student, I rented a 5-1/25 for the modest sum of $65 per month, on Saint-Viateur East at the corner of Saint-Laurent, across from what was then the Peck clothing manufacturing building and is now the Ubisoft headquarters. At that time, Saint-Laurent Boulevard in this sector, between Mount Royal and Bernard, was almost an urban desert, with boarded-up buildings and a few Jewish-owned shops from another age that somehow survived: kosher butchers, dusty grocery stores, fabric shops. The nearby Cinéma Verdi, popular with left-wing intellectuals during the 1960s, had recently closed and moved to the Outremont Theatre. The Lux, a conversion of an abandoned building into a trendy bar and 24-hour newsstand that signalled the beginning of the Main’s return to favour, was not to open until a decade later (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Abandoned buildings, Saint-Laurent Blvd. west side north of Fairmount, Spring 1976. The building on the left was to become Lux nine years later. Photo by Philippe DuBerger

Just behind our apartment building, the Yellow Shoe Company was about to demolish an entire row of triplexes with greystone facades to create a parking lot. If they had survived and been transformed into condominiums, today each unit would sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars (Figure 2).

The neighbourhood west of Saint-Laurent Blvd. was much livelier, with various communities rubbing shoulders on the streets on the way to Park Avenue. Every June, Italians celebrated San Marziale, their region’s patron saint, on Saint-Viateur Street; Greeks, undoubtedly the largest group, who once dominated Saint-Urbain St., Esplanade Av., and especially Park Avenue, where their stores and restaurants abounded; the Portuguese, whose main area was to the south of Saint-Joseph Boulevard. And of course, especially near Jeanne-Mance St., the Jews, mostly Hassidim. Many Jews of the previous generation, who had moved from the neighbourhood during the great suburban migration of the 1950s, remained owners of numerous duplexes and triplexes, mostly as an investment. They rented the poorly maintained dwellings to the newer immigrants and students like me. Once their return on investment dropped, they sold the properties to Greek and Portuguese immigrant families, for whom property ownership was the first stage of moving up in the world.6

This Jewish community was at the heart of my father’s stories of his childhood. My family’s triplex, home to the “Widow Wilson’s Tavern”, located on Laurier just east of Park Avenue, was described as a rare Francophone island in the middle of a Jewish ocean, in which Yiddish was the street language. In fact, he would tell us, at the time (between 1930 and 1950), the neighbourhood contained two different boundaries: one created by Saint-Laurent Boulevard, of course, with its eastern side inhabited by Francophone Catholic workers’ families, and to the west, the streets that formed the heart of Jewish life between the wars, as described by Mordecai Richler and Irving Layton. Less well known, yet maybe even more impenetrable, was the one created by Park Avenue: on the other side was Outremont, the city of the French-Canadian élite. One of my father’s most colourful anecdotes was about one of his sisters – how, as a child she went to play with some girls of her age who lived in Outremont, but after that they were forbidden to play with my aunt again, because she lived on the “wrong side” of Park Avenue.

But the main stories told by my father were mostly about living among Jews. He was even proud of it: the English he had learned playing in the streets or in confrontations, including insults in Yiddish that peppered his vocabulary; also, his role as shabbos goy, which provided him with pocket money from turning on and off the lights during the Sabbath; and learning the art of doing deals, which was quite useful when he was involved in business. My father left Mile End in 1953 to provide a suburban life for his children: the triplex on Laurier Avenue was sold in the early 1970s. Similarly, the original Jewish community massively deserted the neighbourhood during the 1950s, to move to places like Snowdon, Hampstead and Côte St-Luc. They were, in part, replaced by the Hassidim, most of whom arrived after 1945. Like my father, to the Jews who lived in the neighbourhood prior to the Second World War, it reminded them mainly of their early, impoverished years in Canada.

Some of my father’s anecdotes were the mirror-image of those told by Mordecai Richler: how he had to escort his little sisters to their elementary school (Saint-Louis) located east of Saint-Laurent, because they had been insulted by Jewish boys the day before; English as a lingua franca, as French and Yiddish were impenetrable barriers, except for insults; and especially, a shared resentment for the élites of their respective communities.

In the latter case, but this is another story in itself, there was also a symmetry in the equalizing role of two educational institutions that promoted social ascension for the young ‘deserving’ who escaped the masses: Baron Byng High School for Richler and Layton, and Collège Sainte-Marie in the case of my father. For him, as for many others of his generation that flourished in the 1950s and 1960s, whose families did not have the means to send their children to Collège Brébeuf, Sainte-Marie was an important place. The location of the college contributed: it was downtown, on Bleury south of Sainte-Catherine, unlike Brébeuf, which was splendidly isolated on the northern flank of Mount Royal.

In the case of my father, the location of the family triplex was also at an important crossroads. The Park Avenue streetcar led to the college and the temptations of downtown, in just 10 minutes. In addition, the intersection was a transfer point for French-Canadian students on their way to the Université de Montréal, which had moved to the northern slopes of Mont-Royal in 1943. The “Widow Wilson’s Tavern” on the ground floor of our triplex thus soon became a meeting place for the students. That was where my father was to meet Pierre Péladeau, who later convinced him to study law at McGill (in 1946) instead of at Université de Montréal: they shared the same sense of exclusion from the “Outremont-Brébeuf” élite. Their choice, to join the institution par excellence of the English-speaking elite and accept a minority status there which they shared with the Jewish students, was a challenge they accepted.

Figure 3: Park Avenue at Laurier looking east, ca. 1920 – Archives de la ville de Montréal – CA M001 VM098-Y-D1-P025

Increasingly, Mile End took on its destiny as a transitional neighbourhood where each new wave of immigrants left its mark and was then replaced by other new arrivals. The history of the neighbourhood – and especially the cohabitation between all the groups that lived there and how this cohabitation shaped a unique urban space – has always fascinated me.