On February 17, 2017, the roof of the building at the northeast corner of Laurier Avenue and Esplanade collapsed, a victim of several years of neglect. Due to the extent of the damage, the City of Montreal ordered its demolition, taking with it an important witness of the Jewish period of the Mile End. In April 2012, Zev Moses, the director of the Museum of Jewish Montreal, wrote an article telling the story of this building and pleading for its balcony to be preserved. With the generous permission of Zev, Mile End Memories is pleased to present this page of history on its website.

While walking down Avenue de l’Esplanade a few days ago, I passed by a building at the corner of Laurier freshly painted in black, with signs promoting a renovation and 9,000 square feet of commercial space. The sign features a rendering of a theoretical café with dozens of people seated outside on a terrace, enjoying the sun. Such posters would not normally catch my attention, as Montreal is currently in the midst of a real estate mini-boom. But the building that will be renovated is no ordinary building. Obscured by the very sign announcing the renovation stands an unassuming balcony that is absolutely unique to Montreal and Canada.

UJPO headquarters in 2012, then Glatt’s Kosher. Photo : Zev Moses.

The balcony belonged to the headquarters of the United Jewish People’s Order (UJPO) from 1947 to 1950, and then the Farband Labour Zionist Centre from 1951 to 1968. Since 1962, the same building has also housed Glatt’s, a kosher butcher that has occupied this same intersection since 1933. Though there is now a significant Hasidic population just a couple of blocks away, Glatt’s is one of the few remaining Jewish businesses in the Plateau and Mile End that directly descends from the era of Jewish immigration.

Businesses come and go and communities move from place to place. But some landmarks are worth keeping. The balcony at 5101 de l’Esplanade is one of them, as it played a significant role in Canadian and Jewish history. A bit of background:

In the first decades of the 20th century, the East European Jews that settled in Montreal were often impoverished and politically Leftist or radical. Thousands of Jews in Montreal began their lives in the New World toiling in clothing factories, or perhaps as peddlers or petty merchants. They organized themselves politically either according to affiliations already established in their home countries or in new organizations in Canada. Such political organizations were extremely active in the “downtown” Jewish community of Montreal, and were certainly not monolithic; the Jewish Left was composed of a variety of political groups and break-aways representing hotly contested opinions concerning the preferred form of socialism (or sometimes anarchism), the Jewish national language (Yiddish vs. Hebrew), and the preferred Jewish homeland (if there was to be one at all).

On the “right wing” of the Jewish Left, stood Labour Zionists, who were tied to what would become the Labour Party, Israel’s ruling party for three decades. Their followers took over the building on Esplanade in 1951 and led the Canadian Labour Zionist movement, which included the Habonim youth group, a Pioneer Women’s Organization and the Unzer Camp offices. Interestingly, Habonim members at one point became involved in David Lewis’ 1943 campaign as a CCF candidate for Parliament.

Labour Zionist Center, circa 1952. Jewish Public Library Archives.

But Labour Zionists would not have even inhabited this building if it had not been for a historic raid on January 27, 1950 by the Quebec Provincial Police’s “anti-subversive” squad. In 1937, Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis had enacted the infamous Padlock Law, which allowed the government to raid and close politically undesirable organizations for up to 12 months without formally laying charges. The law, also known as “la loi protégeant la province contre la propagande communiste,” also allowed the police to confiscate materials and possessions within the building. The law is historically considered to be one of Canada’s most repressive and most subject to abuse. It was rarely used after World War II, but the UJPO was nevertheless targeted in 1950, during the height of the Cold War. The closing of UJPO headquarters is one of the most notorious instances in which the Padlock Law was enforced.

If the Labour Zionists were on the “right wing” of the Jewish Left, UJPO stood at the left of the Left. It roots were as a Canadian breakaway from the socialist, Yiddish cultural organization, the Arbeiter Ring (aka Workmen’s Circle), which met in present-day La Sala Rossa. In the 1940s and early 50s, the membership of the UJPO may have constituted the largest Jewish fraternal organization in Canada. Closely tied to the Communist Party of Canada, many UJPO members supported Fred Rose, who won a seat in the House of Commons and became Canada’s sole Communist MP in 1943. Even after Rose’s conviction for espionage in 1946, Jewish communists would stay active in promoting their cause.

The UJPO headquarters at 5101 de l’Esplanade was also called the Morris Winchevsky Cultural Centre. UJPO also ran the Morris Winchevsky Yiddish School at 30 Villeneuve Ouest, which no longer stands. UJPO sponsored lectures, concerts, folk choirs, and even summer camps, creating an immersive cultural milieu for its members. One such camp, Nitgedeiget(meaning “Don’t Worry”) welcomed non-Jewish French Canadian children, a rare example of cultural exchange and inclusion in the period.

The UJPO did not support the Zionist cause, instead seeking a solution for the Jewish national question within the framework of the Soviet Union. It supported the creation of Birobidjan – a small Jewish autonomous region in Siberia and promoted Soviet Jewish life through articles in the Vochenblat, an UJPO-associated Yiddish newspaper. Only in 1948, with the creation of the State of Israel and increasing anti-Jewish repression in the Soviet Union, would UJPO tentatively begin to support Israel. By the mid-1950s, following reports of further Soviet purges, UJPO withdrew its support of the Soviet Union.

The January 1950 raid by Quebec Provincial Police coincided with the beginning of the UJPOs slow decline from relevance. As the Soviet Union was increasingly being discredited amongst the Left in the West, the children of UJPO members were also less interested in speaking Yiddish (English was the language of choice) or in radical politics (as they were able to ascend to the middle class). Radical groups were under incredible pressure from legal authorities, including the RCMP, which kept close tabs on the UJPO’s activities. Even Jewish organizations felt a need to distance themselves from the UJPO. The Canadian Jewish Congress, led by Samuel Bronfman, which had representatives of Jewish groups from across the political spectrum, succeeded in pushing out UJPO in 1951.

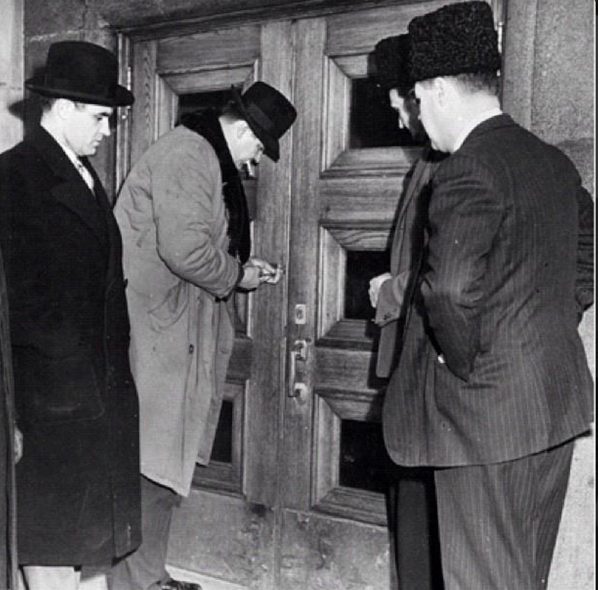

Paul Benoit, chief of the anti-subversion squad of the Provincial Police, padlocking the entrance of the building, January 27 1950. [Paul Normandin, The Padlock Law Threatens You!, Canadian Civil Liberties Union – BAnQ]

The Gazette, January 28 1950.

But the UJPO never disappeared. It still maintains a presence in Toronto today, where it runs a summer camp and the Morris Winchevsky School and Centre, which promotes socialist values and secular Judaism. There is also a smaller presence in Winnipeg and Vancouver. If there are remaining activities in Montreal, I am unaware of them.

Such information is a long preamble to our discussion of the balcony at 5101 de l’Esplanade. But it’s necessary context for understanding why the balcony even exists. Eiran Harris, the archivist emeritus at the Jewish Public Library, and himself a former Habonim member who frequented the building in the 1950s, explained to me the uniqueness and importance of this balcony. When UJPO constructed the modernist building in 1947, they created an auditorium space on the first floor and office space on the second floor. The building features only one balcony with an unusually tall five-foot high wall. Most balcony walls, however, are scarcely higher than 3 feet. So why was the wall so high?

The explanation lies in the politics of the building itself. The UJPO hoped to use the balcony as a space for leaders to give political speeches to crowds below, emulating Soviet and other political leaders of the time who would speak to their followers from similarly elevated balconies. Harris sees similarities in the balcony wall’s uncommon height to that of balconies used for speeches in Red Square at May Day parades. The implication is that a higher wall will protect the speaker (somewhat) from assassination attempts. This explanation may be true, although the high wall may also have just been an architectural device, meant to line up with the lintels atop the first floor windows.

Whatever the reason for the design of the balcony at 5101 de l’Esplanade, its very existence was emblematic of the outlook of the United Jewish People’s Order, and shows a “Jewish” building whose form followed function. In the coming months, Glatt’s butcher will move to a new venue and the building’s renovation will likely mean the disappearance of all physical signs of this unique story.

When I think about the preservation of this building, I am immediately faced with some questions: When does the need for preservation trump the fostering of street life? Should we preserve buildings that are unattractive? And what if a place only maintains meaning for a small number of people?

Even though the present version of the building is arguably ugly, and the alternative proposed by the developer will most likely effect an improvement to Laurier’s street life, it seems imperative to me that the UJPO balcony (at the very least) should be preserved.

Some would say that this defense of a mere balcony is just another example of misplaced nostalgia for groups and movements that are no longer relevant. Groups like the UJPO and the Farband, however,were very important in their own time and represent a piece of the complex pantheon of Montreal’s Jewish life in the first half of the 20th century. To ignore these movements, their stories, and, yes, their physical imprint on our urban fabric, is to simplify Jewish, Canadian and Quebec history as well as the diversity of Montreal. In this case, a balcony is not just a balcony.

First Publication : 20th April 2012. http://thirdsolitude.tumblr.com/post/21450294508/notjustanotherbalcony